AboutEssays1991Which Came First?

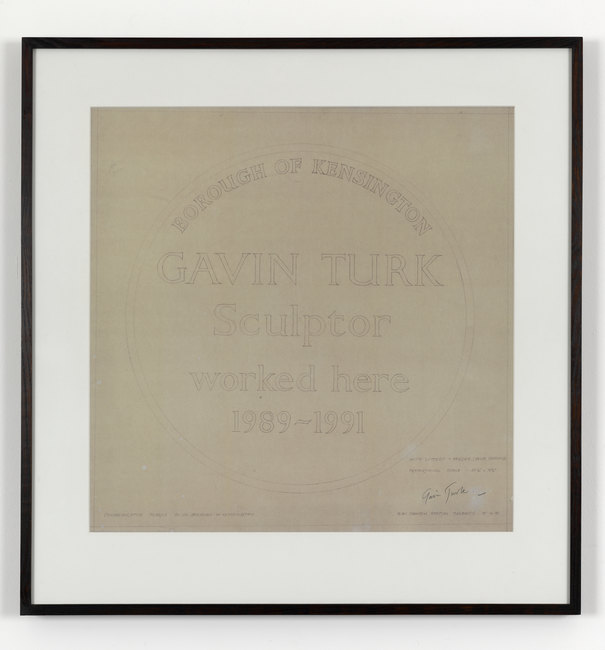

To begin at the end. In a sky-lit wood-panelled room inside the Royal College of Art mounted on an otherwise empty wall in an otherwise empty room, a blue ceramic English heritage plaque reads “Gavin Turk, Sculptor, worked here 1989 – 1991”. A commemoration of a life, it marks the presence of the artist with the most powerful and evocative of the tools that might be at his disposal - his absence. The curtain has fallen. The titles are rolling. Gavin Turk has left the stage. Death as performance. While the absence of the artist, we make the art.

The artist is no more and all that is left for the audience in this empty white space is to reverently imagine the work which once filled this space, while apprehending that the emptiness is the work. And so material object of the plaque frames the space and the art work frames the artist, the one somehow preceding the other in an elliptical sleight of hand, as the end frames the beginning. The artist is dead. Long live art!

To kill yourself off before your career has even begun is a particularly punk thing to do (never mind that an unintentional consequence of the piece was that it cost Turk his degree). Even Sid Vicious managed to produce a slim body of work before his bloody act of self-immolation.

Neither overtly political nor filled with burning intensity nor sneering disdain, what specifically runs through Turk’s work is a quiet psycho-existential angst that says something about all of us in the first decades of a new millennium where all is not half as brave and shiny as we were promised and which finds us on the one hand wanting in desperation to destroy the dream and on the other, equally desperately trying to hold onto it.

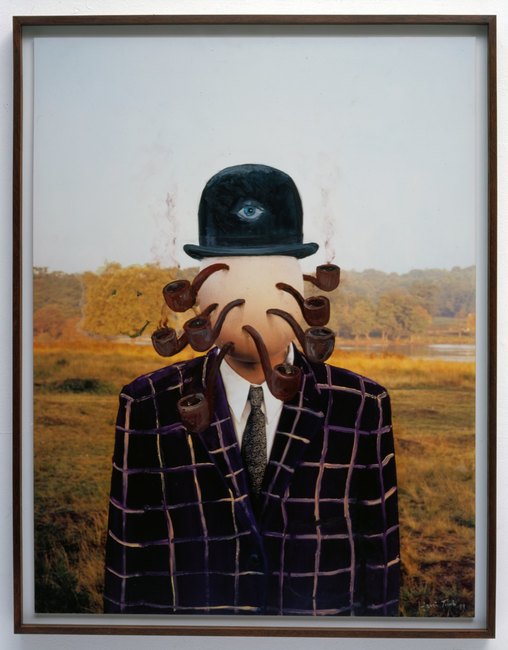

Belonging to a tradition that seeks to critique and challenge what can and cannot be called art which also includes Beuys, Duchamp, Broodthaers, Klein and Manzoni, in Gavin’s work the pipe-smoking intellectual is given an egg for a face and many pipes to chew on at once. Detritus from the street – melons, burnt matches and two pence coins – is cast in bronze as traditional systems and establishment values are turned into surreal jokes intended to reveal all that is hollow within.

Nor is it any accident that Turk is also a fan of Beckett to whom he plays homage in his absurdist puppet show, “Waiting For Gavo”.

A playful, anarchist mischief-maker, in 1998 Gavin turned up to the private view of Saatchi’s now legendary/notorious Sensation show at the Royal Academy, dressed as a tramp, replete with newspapers stuffed into the holes of his falling apart shoes in – the “starving artist” thrown amongst rich collectors, Daniel to the lions – in a move that caused as much embarrassment as it did entertainment, his newspaper stuff shoes and piss-stained trousers (the artist’s own) all a bit too real for some.

Disruptive, subversive, the child who persists in asking difficult questions, the merry prankster mischievously picking at the fabric of tradition, of convention, of preconceived ideas…for all his love of absence, somehow Gavin Turk persists like an indelible stain. Regardless of who or what happens to be in fashion, he just will not go away.

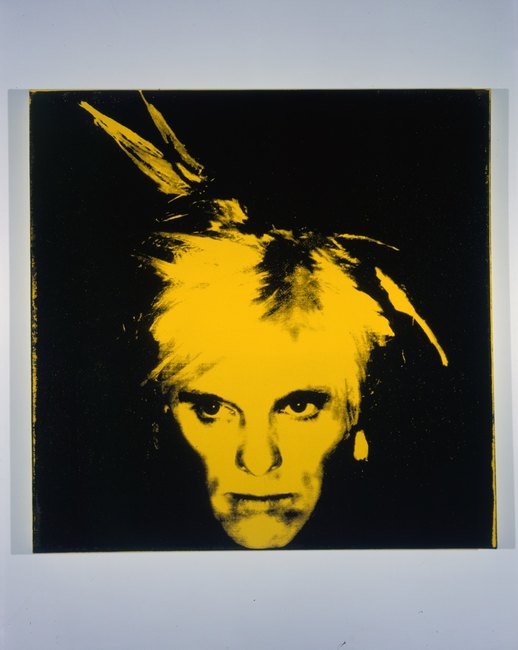

Meanwhile, in Turk world, all art is punk because all art is necessarily fake. It is all represented, copied, a fragment of an unseen whole – a joke on the viewer, bringing into question both perspective and perception and the by presenting something that is not. Yet behind it’s fake-ness, or perhaps because of it, is the same question repeated down the line from the myth of Zeuxis and Parrhasios to De Chirico, Magritte, Klein, Warhol not only through art history but philosophical history and indeed human history; how can we know what is real? And yet through and in and of the fakeness of art lies the possibility of a cool objective truth, which might be reached, as pointed out by William Blake “if (only) the doors of perception were cleansed” for then, “man would see everything as it is; infinite.”

The point being that they are not cleansed but dark and smoky - more opaque than transparent, like the glass placed in a frame over a painting, which reveals most clearly our own reflection. Meanwhile, peering through the doors into the unseen “beyond”, it is not answers that Gavin finds but dead ends and puzzling blind spots, which lead the artist further and deeper into the psycho-metaphysical labyrinth where the monster is the Lacanian “indestructible other” and where it is impossible to tell which came first; the beginning or end, self or mask, original or copy, inside or outside, representation or real, artist or art, chicken or…

Eggs recurs again and again in Gavin’s work. Symbols of life, of creation, of originality, they appear as surreal faces, giant duck eggs, broken shells and in liquid form as mayonnaise and egg tempura. Transforming eggs from the sacred to the profane, the pure to the parasitical, a symbol of creation to something created, Turk takes us on an inventive journey from eggs to eggs cups to fonts.

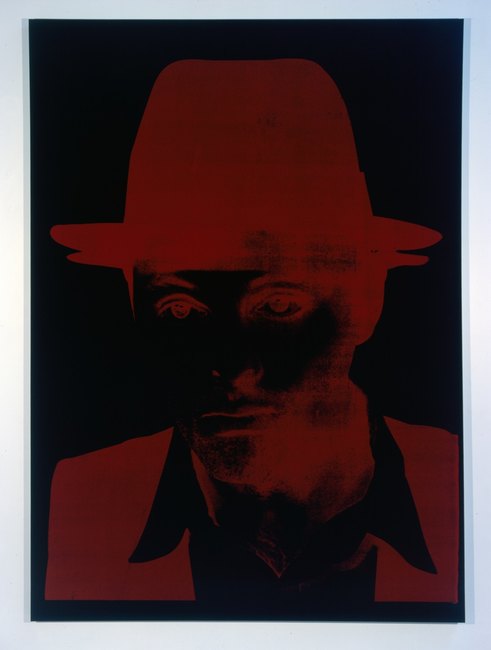

But for Turk – the punk, the hoaxer hoaxer posing as a famous artist - as Beuys, as Marat, as Warhol, as Gavin Turk, the artist posing as the notorious chess-playing hoaxer, The Mechanical Turk – it is not really a question of either/or, real or fake but both/and – real and fake, the gallery and the street, the serious and the frivolous, the original and the copy, the beginning and the end, all pointing to what Kant termed the “noumenal” reality outside of us.

Hence Turk’s interest in trompe l’oeil, in camouflage, in role-playing, in masks and in what the hidden and the concealed is able to reveal. If Turk is a punk, then he is also a shaven-headed Zen monk, constructing visual koans in the form of bronze “wooden” melons or private views where all the exhibits are shrouded, Christo-style, in cloth or presenting himself camouflaged as Warhol or as Warhol’s gun-slinging Elvis as Sid Vicious, with one hand adding a layer of meaning, with another, taking it away.

Refusing to be one thing or another, eschewing the comfortable in favour of the awkward, Turk’s affinity with punk belongs a bigger narrative – the narrative of the revolutionary, the outsider, the lunatic, the scapegoat, the artist as martyr, offered to the world as the sacrificial “Other” in order to simultaneously remind us of our own inner rebel, while reassuring us of our safe position “inside”. Here, it is not his own death that Turk enacts but that of revolutionary icons, Che Guevara and David’s Marat.

Mythologizing the outsider on the one hand and setting out to de-mythologize him on the other; can the artist, or the punk or the outsider really save us - let alone himself - Gavin’s work wants to know? In Window, which shows the disembodied head of Turk in a black beret superimposed onto a double-page spread of The Union Jack taken from The Sun, the artist is here to save the world as both war hero and advocate for peace. In Pop, punk is a wax work museum-ified in a glass vitrine; impotent, dead, useless.

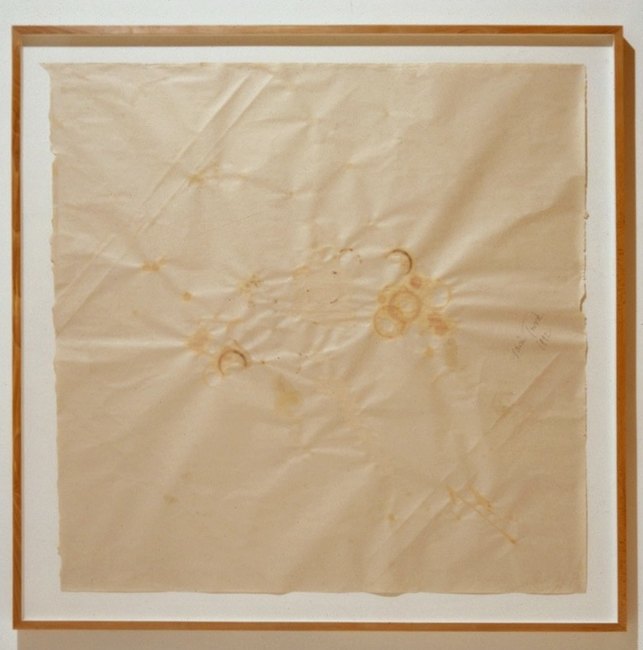

While Gavin’s revolutionary outsiders all met bloody ends, there is no blood in his own ending. Rather, the stains he leaves behind come in the form of the artist’s mark - tea stains, excrement, signatures in egg shells, in blue sponges pinned to the wall, which do not so much replace the art as become it. The artist might be physically absent but his spirit remains through the sacred aura of his stains/signature. Like graffiti, “Gavin Turk was here”, it reads. Authorship is all, it implies. Only who is the artist? Who is Gavin Turk? And besides, Stain 1992 isn’t a real stain but a representation of one left by Giacometti on a napkin after a meal as a joke. What are these stains, these signatures saying but that identity is a fiction?

Derrida called the signature a “parergon” or “parasite” upon the work, which in Greek is “ergon”. Something that confers identity and serves as a threshold between art and not art, signatures are dependent on their authenticity. They must be recognisable through repetition as belonging to a particular artist. But Gavin’s “signature” is his repetition of works by other artists. Even his artist signature is not his “real” one.

Acknowledging the tenuous and fluid nature of identity, Gavin’s work expresses the idea that we frame things but that we are also framed by things. “A Portrait Of Something I’ll Probably Never Really See” shows a face shot of the shaven-headed artist with his eyes closed. Almost like a death-mask, the image is dream-like and tranquil, as if Gavin had reached a Zen-like state of transcendence. But looking inwards, not outwards, what the artists “sees” is that he cannot see himself in all his totality. What he sees is that representation is necessarily false. And this, Gavin’s work suggests, is about as near to any kind of Nirvana he, or anyone else for that matter, is able to get. And yet… and yet, there is that niggling, parasitical “probably”. . .

Derrida described this invisibility at the heart of seeing as an “aporia” or impassable passage. But far from being futile, he saw aporia as necessary to the process of making an ethical decision, even if the consequences of that decision remain unknown. Which brings us back to Cave. All that is left behind of the artist is a memorial to an implied body of work, and by extension, an implied life and worth, while the title, after Plato’s famous allegory, tells of a hidden reality we can neither see nor know. And what of the artist? What of Gavin? He has disappeared into the lacuna, into the beyond, into the hidden reality, behind the curtain covering the canvas, hiding the stage, like Schrodinger’s cat, both dead and alive, chicken and egg, real and unreal both at the same time.