AboutEssays1997Brand You

“Starting today you are a brand. You're every bit as much a brand as Nike, Coke, Pepsi, or the Body Shop. To start thinking like your own favourite brand manager, ask yourself the same question the brand managers at Nike, Coke, Pepsi, or the Body Shop ask themselves: What is it that my product or service does that makes it different?…Take the time to write down your answer. And then take the time to read it. Several times.”

- Tom Peters, “The Brand Called You” in Fast Company, Issue 10

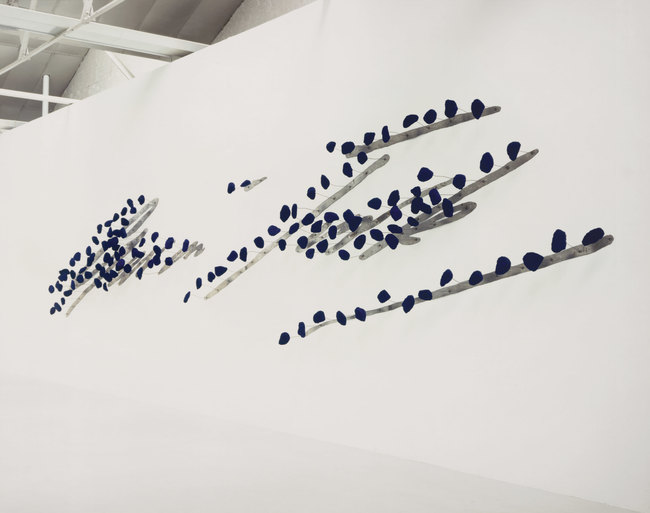

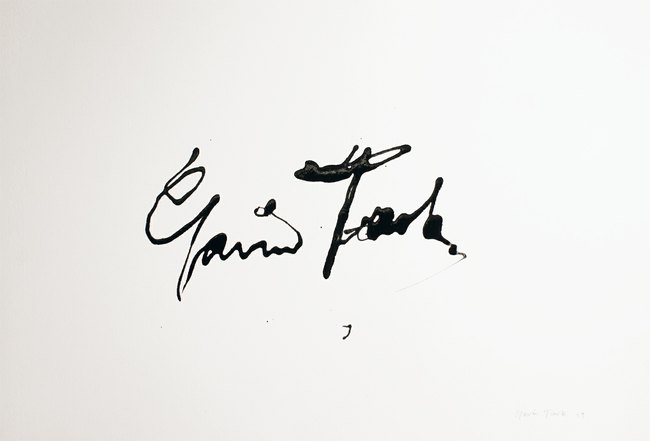

As a culture, it sometimes seems that we value the image of people more than we value people themselves. In response to this, we are inundated with frameworks for “identity management”, self-help advice, and the language of personal branding, while the concepts of success and status in the modern era have increasingly become inextricably dependent on the image we create of ourselves. Wealth and power are predicated on a well-honed ‘brand-you’ to use the unsettling language of management guru Tom Peters.

Beginning with the Enlightenment cult of the personality, which saw characters such as Lord Byron come to personify an early notion of celebrity, as new technologies breakdown the barrier between the public and private, the concept of personality as brand which can be edited and shaped to suit the image of ourselves we’d like to project has pervaded our culture and consciousness to the point where we are so accustomed to it that we have appropriated it into our common vernacular, applied it to ourselves and the people around us, and in some cases elevated it to the supreme arbiter of success. Regardless of inclination or occupation, our collective merit system awards on the basis of fabricated personas rather than authenticity of self.

A number of myths have arisen around the notion of Brand You which seek both to justify and celebrate it as a rational and pragmatic response to a fast paced, attention-scare mediated world, where the power of the image is supreme. Think you are immune to Brand You? Think again.

Myth One: We are all brands

This first assumption is the most perilous. Defining our individual personalities, complexities, and nuances in the simplistic language of branding is not only a misapplication of the definition of brands ; it is a distortion of our identities. The key distinction between brands and personalities is that brands are built top-down; they are collectively decided upon by brand-managers, their values are considered and measured by committees, they are formalized in board rooms and ad agency sofas over cappuccinos and over-priced catering. Personalities are created bottom-up. We are products of our unique histories, our experiences, our relationships, our geographies, our circumstances, our genetics, our world-views.

We lose the organic nature of our identity when we inverse the natural order of how we come to be.

One only needs to look at the plethora of social networking sites to see the extent of our manufactured identities. A generation of youth have internalized the lessons of ‘brand-me’ and rigorously apply them to these ‘identity incubators’. They are thinking about, manipulating, and editing who they are and what image they want to portray before they register their first digital profile.

The great irony in the common (mis)application of brands to personalities is that while individuals stamp out the genuine and natural elements of their identities, brands are desperately trying to become more like humans in order to create stronger emotional bonds. Brands have been humanized, empathized, and personified in the hopes we will choose them over their less human rivals. They have evolved from the old-school notion of the ‘unique-selling proposition’ towards a more complex, multi-dimensional narrative. As brands become more like humans, humans have tried to become more like brands – self-edited, pruned, hyper self-aware – resulting in shallow identities that are often not even as interesting or nuanced as the brands contrived in marketing laboratories.

Myth Two: Personality brands help us navigate within society

In extolling the virtues of personality brands, we are taught to believe that clearly delineated identities not only help us determine who we are; they are sign-posts for the outside world to know what we represent. In practice, when we consciously fabricate our identities, in a social arena of other pre-fabricated identities, we collectively reduce our interpersonal relationships to commoditised transactions.

The people we spend our time with, who we are seen with, whose pictures occupy the precious real-estate of our social networking profiles, are vetted not by our genuine, altruistic desires for friendship, but the symbolism they emit to the outside world.

The other inherent fallacy is our belief that we determine decisions about our identity in complete isolation. This forgoes a fundamental truth of identity: we are formed not for people but because of people. Our identities do not exist independently of concomitant actors in a social world, but because of exposure, interaction, and interdependence.

The transactional nature of relationships and the artificial belief in our independently created identities corrodes our intentions towards each other. We relegate treasured relationships to curated accessories that either hinder or augment our personas. Once we start treating each other like joint ventures in a branding exercise, we start denigrating the very edifice of human relations.

Myth Three: Creating personality brands differentiates us

In the collective race to find the thin layer of identity that represents us, we are constantly barraged with the same stimuli. What is considered aspirational in one social circle is the result of cues and cultural reference points targeted by the media to that very audience. Paradoxically, as we forge our brands, our identities look strikingly similar to the person next to us. The clairvoyant investment banker, the billionaire real estate mogul, the aspiring hip hop artist, the stay-at-home mom turned novelist are all reinforcing their archetypes (or more accurately, stereotypes) rather than differentiating themselves from the mould.

When everyone is applying the same aesthetic strategies, with the same props, affected by the same trends, in hopes of appealing to the same audience, we homogenise the personalities that should be the source of creative variety in our culture. Even the dissidents of our counter-cultures have veered away from their once idealized purpose of subverting the mainstream; they evaluate their success by the cultivation of their brands, their commercial prowess, and their popular legitimacy.

As our mavericks are muted, the rest of us look around at our generic brands and find ever more novel ways to stand out. Our increasing exasperation leaves us feeling alienated and ineffectual, as we replace our identities for attention-seeking stunts, distinct idiosyncrasies, and peculiar behaviours that will have us remembered by others, but forgotten by ourselves.

What must be done? Does it even matter?

As language philosophy suggests, the words we use to articulate our world are reflections of our societal values, and they propagate those values in a powerful way. As Wittgenstein famously remarked, “Like everything metaphysical, the harmony between thought and reality is to be found in the grammar of the language.” The words we use determine our behaviour and ultimately culture. We cannot talk about identities as brands without reducing our behaviour to brand mimicry.

The creative industries that play a formative role in culture creation, in defining the grammar of language – from art to journalism to advertising to entertainment – are co-authors in staking out our collective values. They can help champion a return to embrace what’s beneath the social veneer. But there is also an onus on us as individuals, as consumers, as identity-generators, to become conscious again of how we come to be. We must recognize that who we are is a result of the communities we are a part of. And the quality of those communities is a direct result of our contribution. There is a fluidity and flux, a give-and-take, that defines our social fabric. The narcissism of brand-me must give way to a broader social purpose.

There is no easy way out of our current situation. The idiom of brands as personality is well entrenched. However, we can start to question the values it dictates – we can foster a consciousness of the effect of fabricated identities and the misapplication of branding to personalities. After all, recognition can be the strongest form of rebellion.