AboutEssays2005Chewing Gum

There is no real reason why chewing gum in its modern form should exist at all. At the time it was invented it served no purpose beyond the satisfaction derived from purchasing and owning an object (albeit briefly), and the pleasure to be had in exercising one’s lower jaw. Any functionality that is now ascribed to modern day chewing gum has been grafted onto it since its first appearance 120-odd years ago.

Apparently cursed with a lot that plumbs the depths of banality – there can be few fates less appealing than being placed in the mouth to be masticated into tastelessness before being spat out – chewing gum has somehow achieved iconic status. The frivolous nature of its existence, its record as one of the first mass-produced products of the twentieth century, and its standing as the epitome of inbuilt obsolescence have assured its place as a poster boy for the consumer culture of the developed world.

It was not always thus. The first chewing gum was extremely practical in nature. Archaeologists working in Sweden and Finland have discovered pieces of birch bark tar imprinted with human tooth marks made over 5000 years ago. Our Neolithic ancestors are believed to have chewed the medicinal tar as a way of warding off tooth ache and sore throats.

Since then, there have been many resins, grasses and other plants made into some form of gum so that their healing properties might be released into the body. However, it was the American Indian habit of chomping on a resin derived from the sap of spruce trees that paved the way for chewing gum as we know it. Settlers in New England began to mimic the practice to such large numbers that one John Baker Curtis began to market strips of his home-made ‘Curtis’s State of Maine Pure Spruce Gum’ for two a penny in 1848. So successful was the product that he was able to build the world’s first chewing gum factory four years later. However, for all its antiseptic qualities, spruce gum did not have an appealing flavour and Curtis soon moved over to the production of gum made from paraffin wax whose own less than thrilling taste was masked by the addition of vanilla or liquorice.

The development of chewing gum might have stopped right there had it not been for a 1869 meeting in New York between exiled former president of Mexico, General Santa Anna – Davie Crockett’s victor at the Alamo – and compulsive inventor Thomas Adams. Santa Anna was keen to raise money to fund an unlikely armed insurrection against the Mexican government by promoting chicle – a latex tapped from the chicozapote tree – as a cheap substitute for rubber in the manufacture of car tyres.

After months of failed attempts to create a chicle rubber suitable for the motor industry, Adams and Santa Anna gave up on the enterprise. It was only when the former witnessed a young girl buying a pennyworth of paraffin wax gum (which the shop owner described to him as ‘pretty poor’) that he hit upon the idea of experimenting with chicle as a chewing gum. He came up with a putty-like material that could be rolled into a ball in the mouth and, by February 1871, launched it in a single shop in New Jersey. It was tasteless and had no health-giving properties but it was recognisable as chewing gum and since it was better than the wax chewing gum on offer, people bought it. It was sold by the stick as ‘Adams New York No.1 – Snapping and Stretching’. A picture on the box showed City Hall, an instantly recognisable building in America’s most exciting city. Chewing gum had taken the first step in its long journey of appropriation of celebrity as a marketing tool.

Adams and other entrepreneurs were soon adding flavours to the gum to make it more appealing. Early experiments saw the inclusion of sassafras root bark, liquorice (again) and tolu, an ingredient then used in cough syrup, a move that gave back to chewing gum its original medicinal function. Pliant experts were soon on hand to recommend the use of gum to relieve thirst, freshen breath, calm nerves, ease sore throats and quicken the appetite.

Competition from other brands spurred Adams to advertise on huge billboards on Broadway, bringing gum into the public space and consciousness as never before. William Wrigley went one better, erecting a line of 117 billboards along a New Jersey railway track on his way to becoming the United States’ largest purchaser of advertising.

Since chewing gum was a product essentially without a purpose it acted as a blank page onto which manufacturers painted the fantasies of consumers. A brand called Kis-Me played on the sexual appeal of placing something in one’s mouth. William White, the first man to market a mint gum, was also the first to make a link in the minds of potential customers between the chewing of gum and fame, fortune and success. In 1898 he began to get his gum into the mouths of the beautiful people, even managing to foist a stick on the future Edward VII whilst on a trip to England. The ploy was to be expanded later by the mass theft by the industry of an idea used by bubble gum makers: the issuing of free cards depicting movie stars, baseball players, national heroes and prominent millionaires.

Gum first crossed the Atlantic in large quantities in World War I when more than four million packs were sent to troops by the American Red Cross. However, it was the GIs based in the UK in World War II who turned Britons on to chewing gum in huge numbers. It has since crossed the globe so that today there are over 500 companies making chewing gum in 93 countries (though, famously, the substance is banned in hyper-neat and tidy Singapore – those caught smuggling it in face a 12-month prison sentence). Chicle is almost a thing of the past, however, since almost all chewing gum is now made from synthetic substances such as vinyl resins or microcrystalline waxes.

The relative cheapness and easy portability of gum has contributed to its use becoming routine for large swathes of the world’s population. As a source of displacement activity and instant gratification it has only the cigarette to rival it. However, despite chewing gum’s acceptance into mainstream culture and its tooth-whitening, breath-freshening image, there’s still something about it that suggests its home is on the wrong side of the tracks. Mix some surly body language with a slow deliberate chew and gum becomes a vehicle to express aggression and rebellion. This perhaps goes some way to explaining its popularity amongst successive generations of the young.

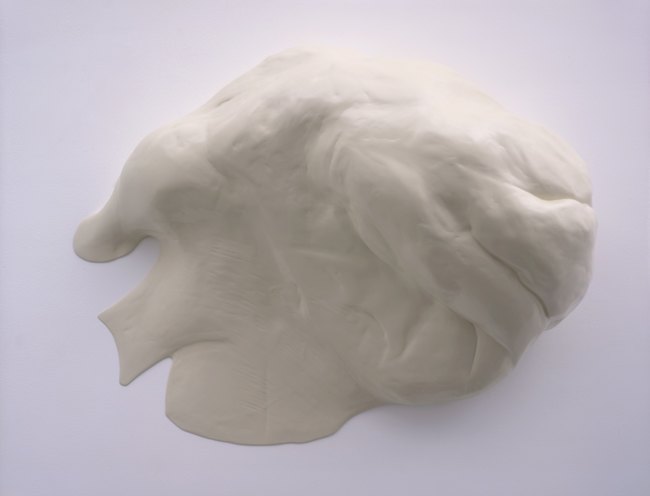

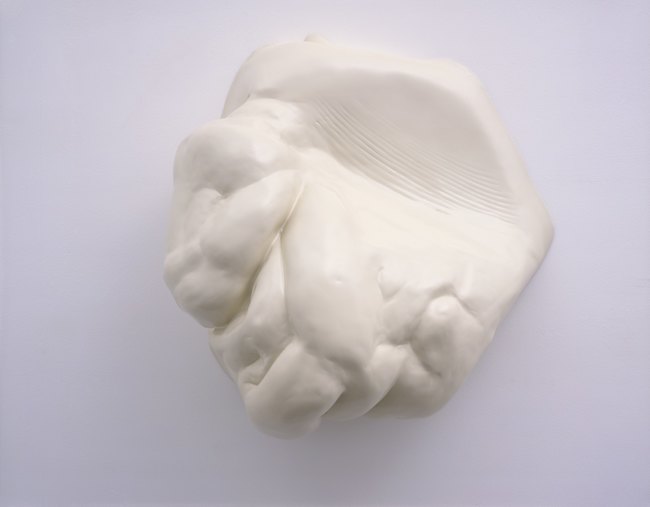

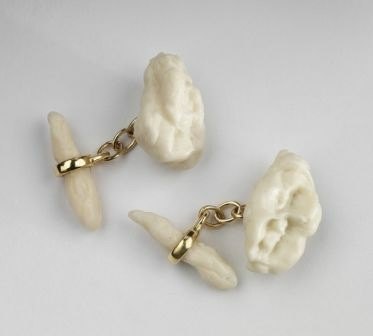

More surprisingly, once used, chewing gum is capable of its own feats of artistic self expression. Unlike its inert uniform pre-masticated state, used gum is uniquely shaped by the mouth of the individual who chewed it. Spurned by the user, it then takes its revenge wherever it is discarded, clinging limpet-like on pavements, park benches or Lonny Donegan’s bedpost. It punishes the species that created its all but meaningless existence by inflicting upon it its inherent ugliness. More potently still, it remains poised and ready, day and night, to stick to any careless shoe, hand or even backside with which it comes into contact. In 5000 years, archaeologists will find it and will make a pronouncement about our era that we may not wish to hear.