AboutEssays1999Guevara In Art

In a TIME cover article of August 1960 Ernesto (“Che”) Guevara, was described as the “Brain” behind Castro’s Cuba. Whilst Castro was the “heart, soul, voice and bearded visage”, and his Brother Raul was the “fist that holds the revolution’s dagger”, Ernesto took control of the countries ideological and fiscal policies, although in a particularly maverick way.

Whilst recent artistic projects, not to mention notable biographies, have sought to put the brain back behind the floating iconic face, it may still seem peculiar to hear Che described first and foremost as a brain, with Castro taking the place of the visage. Furthermore, the TIME front cover of the 8th August 1960 jars with our contemporary imagination. The Che pictured in realistic shades and hues is not the Che of Alberto ‘Korda’ Diaz’s ubiquitous photograph; not the statuesque Che, staring enigmatically off into the distance, not forever young, melting into the mane of his hair and beard as a crown of thorns or a halo, but smiling, engaged and ruggedly lined. TIME, however, did prefigure the objectifying of Che, with the all attendant problems for historical truth, by remarking that he is “the most fascinating, and the most dangerous of the triumvirate” and that his smile has a power that “women find devastating.”

In the same issue of TIME, there is piece on Marilyn Monroe as she prepared for “The Misfits”, directed by her husband Arthur Miller. The piece poignantly points to cracks appearing in Monroe’s façade. She is painted as a neurotic figure who reflects the character she is playing, Roslyn, as a “fractured, manhandled woman.” Monroe was found dead almost exactly two years later, “The Misfits” being her last film.

“Che Guevara was the Marilyn Monroe of Marxism, an empty receptacle for fantasy” writes Jonathan Jones in his review of Gavin Turk’s 2001 post-Beuysian teach-in, “The Che Gavara Story” [sic]. This seems an easy association, one which we can accept without flinching. Yes, Hollywood’s tragic heroine of Che’s hated America and Cuba’s martyred hero seem to be part of the same breath. And yet it is only their emptiness which is the same. It is only the remarkable similarity of their magnitude as ciphers that makes this connection so easy. Beyond this they are, of course, complete opposites. It is one thing above all that makes the Marilyn/Che comparison so natural, and that is their reduction to a single image; Warhol’s image.

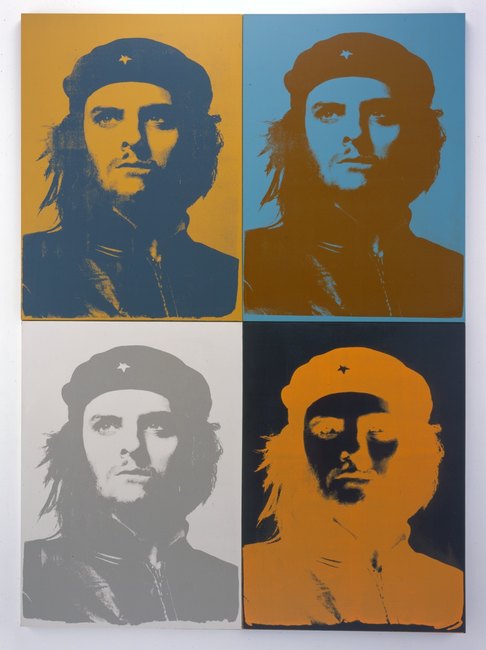

Within the course of ‘The Gavara Story’, Jones reports, the question was raised as to why Warhol never “did depict Che”. Jones recalls that in fact Warhol had depicted Che, in his 1965 film The Life of Juanita Castro, but not as the Che of Warholian silhouette that we all know. We may in fact be forgiven for thinking that Warhol had in fact depicted Che in typical multicoloured silhouetted fashion. Trisha Ziff has tried to establish the origin of the famous ‘faked’ ‘Warhol Che’ and traces the authorship of the image to former Warhol assistant and star of many a Warhol iconic portrait himself, Gerard Malanga.

Of course the notion of authorship in Warhol’s silkscreens is ambiguous and debatable and Warhol allegedly claimed the series as his own after Malagna’s appeal for help following the discovery of the forgery. We may wonder as to why Warhol had not produced an iconic image of Che himself. As Jones’ opening assertion suggests it would appear to have been an obvious choice. Perhaps Che had not captured Warhol’s imagination, perhaps, as the campery of Juanita Castro would suggest, Che did not possess the compellingly deep one-dimensionality that Warhol usually sought, or perhaps he simply had not got around to it before the forgery and other similar versions had appeared. Forgery or no forgery, Warhol had already made an image of Che; for all images that appear on t-shirts, the icon of the Korda photograph, the Jim Fitzpatrick posters, the “devastating” Hollywood smile, could all be said to be Warhol’s in a crucial way.

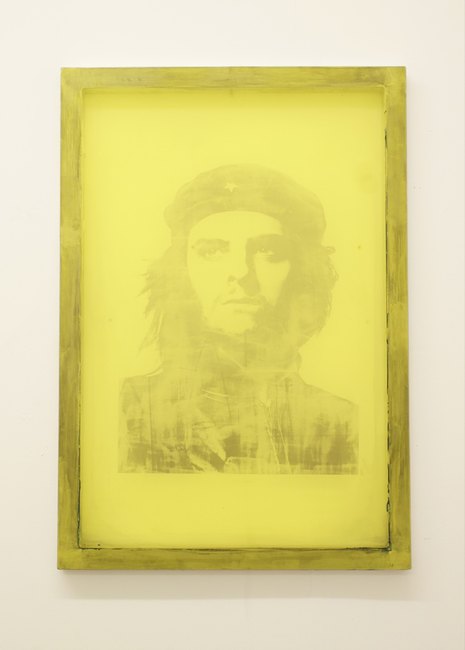

When Jim Fitzpartick made possibly the most famous silhouette of Che using Korda’s “Guerrillero Heroico” in 1967 there was no mistaking the presence of Warhol. Warhol, as a signifier for repetitious celebrity, as an embodiment of one-dimensional contemporary iconography came before and after the flowing of Fitzpatrick’s icon into contemporary consciousness. Although those dependent on the art market might like to dispute it, Warhol’s signature was not so much a moment of artistic authoring, but a statement about celebrity and value itself. The content of the signature as repeated, as the image of Che or Monroe repeated, existed in the act of repetition itself rather than its particular signification. The proliferation of a Warhol image enacted its death with the morbidity which occurs with the uncanny fascination of recall and distancing. The attention to the particular and the generic which exists within a Warhol series is like that which makes the familiar strange, like a word or name repeated without context until the tongue becomes awkward around it. The morose nature of repetition leads, arguably to the limit event of Warhol’s “Death in America”, series. Hal Foster asserts, in his essay titled after the series, that;

“Somehow in these repetitions, then, several contradictory things occur at the same time: a waning away of traumatic significance and an opening out to it, a defending against traumatic affect and a producing of it.”

In the waning of the traumatic, Foster is referring to Warhol’s own remarks about the diminishing effect of the “gruesome” when viewed “over and over again.” However, Foster also perceives these sites of repetitious unpleasantness to be instances of ‘traumatic realism’ – a reenactment of the death depicted in the horror of the semelfactive seeing again and again. Such a trauma is reminiscent of the film ending of Graham Greene’s “Brighton Rock” in which Rose goes to play a recording of Pinky’s voice to console her after his death, only to hear a partial truth as the record hits a scratch and repeatedly jumps with static rupture saying ‘I love you’.

Similarly, the protagonists of Warhol’s portraits become forever frozen in a permanently repeated death with the question of salvation or damnation deferred. A viewer of “Brighton Rock” is forced to relive a trauma both numbed and accentuated by the dramatic irony of the situation; we know that if the record were to play Rose would not hear Pinky say how much he loves her but would instead hear him tell her “I hate you, you little slut”.

The initial horror of the dramatic realisation, as the record is played and the abrupt relief of the jumping needle, both softens the feared finality of the death of the illusion and at the same time deepens the trauma by continually reminding us of the emptiness of the words embedded in Rose’s mind. Similarly, the banality of Warhol’s repetitive and softened, ‘Hollywood’ endings are in themselves traumatic instances. A singular image of Monroe as colourful clown could have been seen as a celebration, or at least a monument to mourn, multiple Monroes (proliferating forever more at grotesque rate of speed) become a yawning sorrowful emptiness, a morose stuck record.

As Hannah Charlston says in her introduction to the catalogue which accompanied the V&A’s exhibition “Che Guevara: Revolutionary and Icon”, “The story of the Che image is in part the story of the growth of visual literacy.” Whether or not Che was a good man or a bad man, a hero or a psychopath, the trauma which is repeated in the proliferation of the image through a continual reordering of the linguistic, denoted and connoted, as Barthes might suggest, results in a deadening loss of aura and history. The multiple instances of Che’s reworking in poster form, by activists (on all sides), admen, artists, designers, becomes an essay in contemporary textual fracturing. Following on from Barthes, the retelling of Che as image may indeed be best understood as a symptom of our visual literacy, our ability to digest and read all as textual mirror.

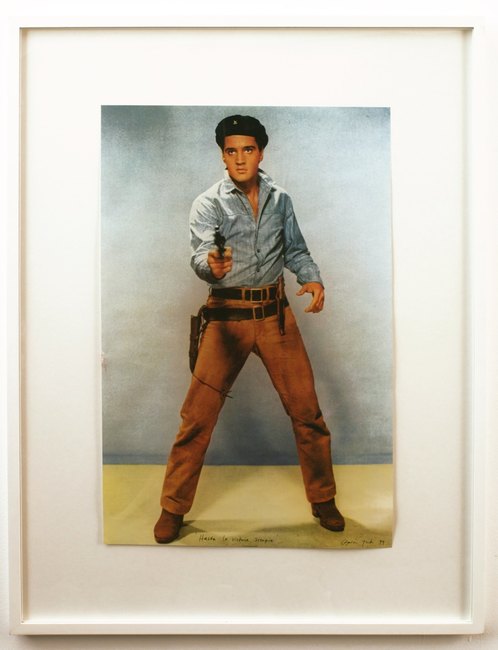

Discussing Che as icon is becoming as clichéd as the image itself. If one wants to discuss the rabid force of commercialisation, the ubiquity of celebrity, the reduction of the revolutionary spirit to image, then ‘Che’, via Korda, via Fitzpatrik, via Warhol, is too exemplary to ignore. As we attempt to move forward heroically, tragically, romantically, pathetically, tragically, comically, then we may easily find ourselves picturing ourselves as Guevara, in Elvis stance, through Warhol, as an act of trauma magnified; three one-dimensionalities compounding our own.